Applying cylindrical closures

Application of cylindrical closures

Fill height and ullage distance

Post-packaging quality control cork closure assessment

Cylindrical closure types

Cylindrical closures include those made from natural cork, agglomerate cork, a range of synthetic alternatives or glass. Cylindrical closures are closures that are inserted into the bottle neck. The seal is made along the length of the closure with the glass of the bottle. Wines with >1.2 g/L carbon dioxide may require specialised cylindrical closures. This page focuses on the application of natural or agglomerate cork closures to bottled still wine.

Closure dimensions

The natural cork closure used for table wines is usually 44 or 49 mm in length and around 24 mm in diameter. Natural corks can vary ± 1mm in length and ±0.5 mm in diameter. Standard CE.T.I.E (Centre Technique International de l’Embouteillage) wine glass finish bottles have been designed for use with 44 mm length closures. For longer closure lengths (such as 49 mm closures) the bottle neck is more bell-shaped and wider at this depth, particularly with Burgundy shaped bottles, which makes it more difficult for the closure to expand and exert sufficient pressure against the glass to make a good seal.

Cork treatment

A cork often contains around 16-18 mg cork treatment or coating per 44 x 24 mm cork. The treatment lubricates and facilitates entry of the closure into the neck of the bottle (McMahon 1994). Too much cork treatment can result in residual treatment on the surface of the wine and later leakage. Too little treatment can make the cork dry and difficult to insert. Natural closures generally have around 6±2% moisture content and should contain <2 mg dust/stopper. Over-dry or overly wet corks can also result in sealing issues.

Application of cylindrical closures

Once a bottle is filled with wine it can be manually moved to a corker machine or, if on an automated line, is returned to the conveyor belt and then picked up by the ‘corker’ machine and placed on a bottle platform. This platform needs to be adjusted before bottling for the specific bottle type/height in use. A single closure passes from a chute to the four corker jaws positioned near the neck of the bottle. The corker jaws compress the diameter of the closure from 24 mm to about 15-16 mm. A neck-centring device guides the bottle and a pushing pin pushes the cork down and into the neck of the bottle. Corker jaws need to be correctly aligned with the bottle to prevent cutting, deforming or seams occurring in the closure, which can then lead to leakage if the bottles subjected to any adverse conditions.

The closure recovers about 85% of its original diameter after a few hours. CE.T.I.E (1980) recommends filled bottles be kept upright for a minimum of three minutes. Amon and Simpson (1986) recommend that bottles sealed with cylindrical closures be kept upright for at least five minutes and preferably one to two hours after bottling, to allow the closure to recover from compression within the corker jaws and form an adequate seal.

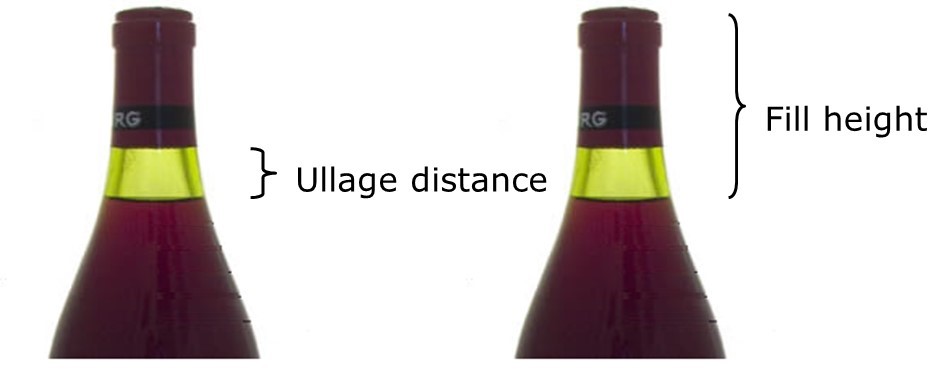

Fill height and ullage distance

The fill height, or the distance from the surface of the wine to the top of the bottle, with the bottle in an upright position, is generally between 55 and 63 mm for conventional glass wine bottles, with a greater distance used for larger cork lengths >49 mm (Riboulet and Alegoët 1994). The average percentage of headspace after sealing under normal conditions, in relation to total capacity, is between 0.1 and 1.0%. A headspace is required in order to allow enough volume for expansion of the wine during storage at 20–25°C. It is important to emphasise the connection between the choice of the cork length, the bottle shape and the fill height. Using an inappropriate cork for the bottle type can easily result in deviations from the required headspace.

The ullage distance is the distance from the surface of the wine to the underside of the cork, with the bottle in an upright position. Australian guidelines state that for standard CE.T.I.E cork mouth bottles, ullage space should be greater than 12 mm at 20°C. Amon and Simpson (1986) also recommend a minimum ullage distance of at least 13 mm (measured at 20°C) for nominal 750 mL bottles.

It should be noted that in previous investigations conducted at the AWRI, low ullage distances at bottling have contributed to leakage problems in bottled wines when subjected to ‘moderate’ heating (~35°C). The wine volume expands with heating, leaving no empty space, and the bottle pressure can increase to levels above 50 kPa. In its Practical Guidelines for Bottling No.1, CE.T.I.E (1980) details the temperature increases required for various stopper lengths at both low and high fill heights for wine to expand and reach the bottom of the closure. This temperature can be as low as 29°C with some combinations. However, if the appropriate closure is used, for wines between 10-16% alcohol, this is normally between 43 and 55°C.

Closure insertion depth

The closure insertion depth is the distance from the top of the bottle to the top of the closure inserted in the bottle. Over-insertion of closures in bottles can decrease the required ullage and may increase the chance of leakage should these samples be exposed to increased temperatures. The stopper once in place must not protrude above the rim of the bottle nor be over-inserted into the neck of the bottle by more than 1 mm.

Filling temperature

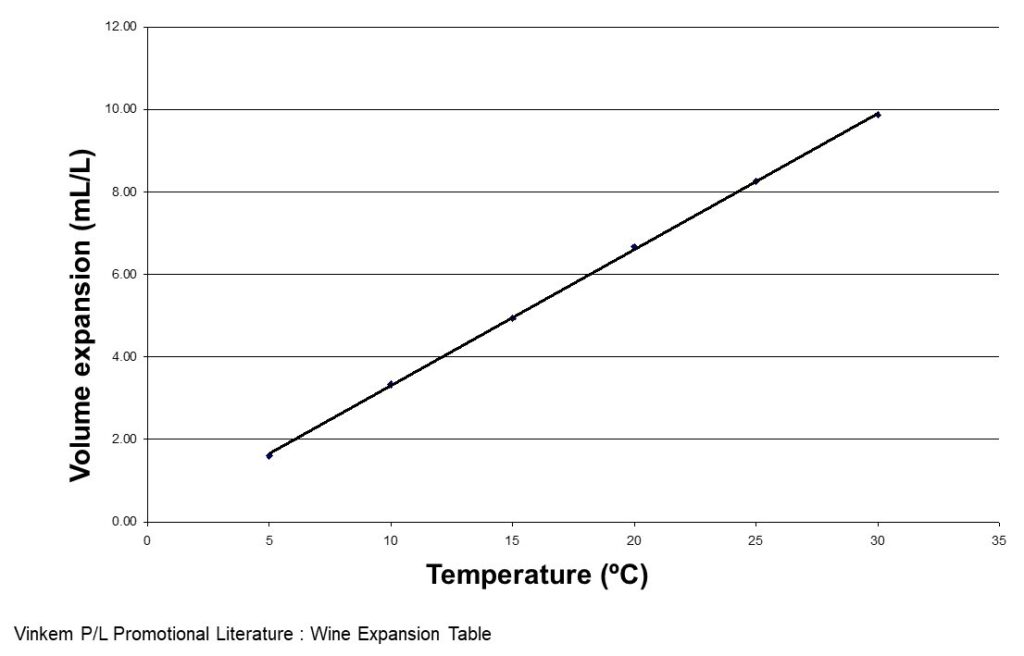

The filling temperature (i.e. the temperature of the wine during bottling) must be taken into account when determining fill heights, to compensate for wine expansion in bottle that will occur when the wine warms to room temperature, and also at the higher temperatures that may be experienced when a wine is transported. A greater ullage distance should be provided for wine filled at temperatures below ambient temperature, in order to allow for the thermal expansion of the wine. An ideal filling temperature is around 18°C. Wines supplied to bottling facilities outside the range 15-21°C may incur fees if the wine needs to be chilled or warmed before packaging. Filling at very low temperatures may also affect label application on the bottles, with condensation interfering with the adhesiveness of the labels and thus labelling efficiency. Some facilities have a heat tunnel that bottles pass through after sealing to dry bottles. Filling at high temperatures may cause physical damage to the filled bottle when the wine cools in storage and draws a vacuum through natural closures.

Wine volume expansion with temperature can be estimated using the below chart from Vinkem.

Further information is available under Wine expansion – this gives a summary of the thermal expansion data for wine, which can be used to predict changes in the volume of wine at various temperatures during storage, as well as to calculate the headspace/ullage volumes required during bottling.

Post-packaging quality control cork closure assessment

Bottle pressure (headspace pressure)

When placing wine in a bottle and sealing with a closure, a sealed pressure system containing a liquid and a gas phase is created. This is affected by changes in temperature such as during transport or storage, with the wine and gas expanding or contracting in volume and decreasing or increasing in pressure. In some cases the wine can expand to reach the underside of the closure and exert a hydraulic pressure, with wine moving into the stopper, and/or causing a leak, which can then affect the performance of the closure. A sufficient headspace should be provided to accommodate these temperature changes without the bottle pressure rising above 1 bar (100 kPa).

Cork Supply Australia recommends internal pressures of filled bottles of wine should be <20 kPa at 20ºC, with Amon and Simpson (1986) suggesting that leakage is likely to occur above a ‘critical pressure’ of 200 kPa. The best way to eliminate positive headspace pressure is to eliminate all pressure and create a vacuum in the bottle. After filling, the bottles are positioned under the closure machine, and the air in the neck is extracted by a channel linked to a vacuum pump, and the closure is inserted at the same time. This creates a slight negative pressure. The average bottle pressure under vacuum fill is -5 kPa, and under non-vacuum normal fill is 15 kPa.

Extraction force

The extraction force is the longitudinal force required to remove a cylindrical closure. The results provide an indirect measure of some aspects of cork performance, particularly with respect to the properties of their surface coating and their resilience and elasticity. Extraction forces should be measured more than one hour after sealing. McMahon (1994) and CE.T.I.E (2008) specify the following extraction forces for different length natural or synthetic cork closures:

| Natural closure | Synthetic closure | ||

| McMahon | CE.T.I.E | CE.T.I.E | |

| Closure length (mm) | Extraction force (N) | Extraction force (N) | Extraction force (N) |

| 38 x 24 | 230 – 400 | 120 – 350 | |

| 44 x 24 | 250 – 450 | 120 – 400 | 100 – 450 |

| 49 x 24 | 270 – 480 | ||

It is the AWRI’s experience that wine travel/leakage may contribute to a reduction in extraction force values, due to the lubricating action of wine between the cork and the bottle bore, and the softening effect on the cork as it absorbs wine through its longitudinal surface. Conversely high extraction forces can indicate closure/bottle misalignments and can pose safety risks due to the high force required to remove a closure.

References

Amon, J.M., Simpson, R.F. 1986. Wine corks: a review of the incidence of cork related problems and the means for their avoidance. Aust. Grapegrower Winemaker (268): 63-64, 66-68, 71-72, 75-77, 79-80.

International Technical Centre for Bottling. Cetie: Free voluntary standards for glass and PET packaging.

Macmahon, D. 1994. Supplier quality management: corks. Gibson, R. (ed.) Quality management seminar: proceedings of a seminar; 12 November 1993;, Seppeltsfield Winery, South Australia, Adelaide, South Australia; Australian Society of Viticulture and Oenology

Riboulet, J.-M., Alegoët, C. 1994. Technical difficulties of corkage: 6. Sealing faults. Practical aspects of wine corkage. English ed. Chaintré, France: Bourgogne Publications: 211-219.